A bottle of Inca Kola with a glass.

Es nuestra, La bebida del Perú (It’s ours, the drink of Peru)

– The slogan of Inca Kola in 1990-1995

In 1910, an English immigrant couple who went by the name “Lindleys” settled in Rimac, one of the oldest and most traditional district in Lima, Peru. Living closely with local beverage makers who had inherited ancestral drink formulas for generations, Lindleys learned to create beverages of their own, mixing local concoctions with new flavors, ingredients and different levels of carbonation. Lindleys’ experiments went on, until twenty-five years later, in 1935, when they finally created what would be known as Peru’s national drink, Inca Kola. While It came out forty-nine years later than the world-renowned soft drink giant, Coca Cola – officially invented by an American pharmacist and ex-Confederate Civil War veteran John Pemberton – was first officially produced, Inca Kola managed to be one of the few local brands that defeated Coca-Cola in its domestic market. Even to this day Inca Kola still tops the soft drink sale rankings in Peru, and its brand exported throughout the entire South America. One of the key factors behind such great success of Inca Kola was aggressive marketing campaign targeting Peruvian nationalist sentiment.

One of the labels of Inca Kola featuring an Incan man. Photo courtesy of http://imgarcade.com/inca-kola-label.html

Inca Kola label depicting an Incan woman. Photo courtesy of http://imgarcade.com/inca-kola-label.html

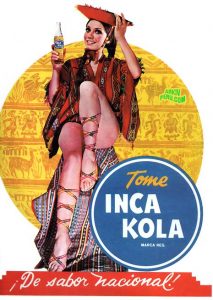

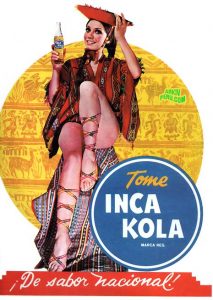

Pablo Nano Cortez, the chief economist at Scotiabank Peru, says that ever since Lindleys – who officially chartered their company as Corporación José R. Lindley S.A in 1928 – started to market Inca Kola as a brand, they constructed a nationalist image of Peru around it: something only Peruvians can offer. Even the name itself invokes the proud heritage of Inca Empire, which is still considered by Peruvians as one of the most significant root of their culture and national identity. The labels of Inca Kola are adorned with Inca symbols, or faces of man and woman from Inca Era. The color of the drink was also designed to be the allusion to well-known stereotype of Inca Civilization – the Inca gold. Even the first delivery trucks exclusively for Inca Kola were said to be painted with national colors of Peru – red and white. Advertisement posters for Inca Cola often featured indigenous Andean women, or non-indigenous women with traditional Peruvian/Andean attire.

Inca Kola advertisement featuring a woman with Andean attire, sitting in front of Inca mural background. Photo courtesy of https://www.pinterest.com/pin/95208979592204617/

The nationalist sentiment behind Inca Kola marketing grew more aggressive when Coca-Cola started to engage total soft drink market warfare in Peru against Inca Kola during the 1970s’. While entering the Peruvian market since 1935, it was not until the 1970s’, when this American soft-drink giant started to prove itself to be a tough challenger to decades-long domination of Inca Kola in Peruvian market. While Inca Kola controlled 38% of the soft drink markets of Peru, it was threatened by Coca-Cola’s well-adjusted localization strategy, which even involved changing its secret formula to be more suitable to Peruvian taste. Lindley Corporation reacted to such strategies by doubling down on its already aggressive nationalist marketing. Peruvian names, ingredients and flavors started to be the central parts of promotion and advertisement of the Inca Kola. Slogans which emphasized Peruvian national identity appeared much more frequent ever before. This trend went on for decades, until 2006. Explicitly nationalist-driven marketing ploy supported by Inca Kola’s own distribution system and sales force which extended throughout the entire country ultimately resulted in long-time domination of Inca Kola within Peruvian market. Until the end of 1990s’ when Coca Cola and Lindley Corporation stroke the deal that established joint-venture business partnership, Inca Kola owned lions’s share of 35% market share, whereas Coca Cola got only 21%.

La bebida del sabor nacional (“The drink with the national flavor”)

Es nuestra, La bebida del Perú (“It’s ours, The drink of Peru”)

De sabor nacional! (“Of the national flavor!”)

As of 2012, it was reported that Inca Cola controlled the total market share of 26% which is narrowly followed by 25.6%, exceptionally out-shining other local brands throughout Latin America where they have not fared well against the total domination of Coca-Cola. Johnny Lindley, the second CEO of Lindley Corporation, stated that Inca Kola remains to be the drink that found a permanent place in Peruvians’ heart.

“Because we knew how to communicate that we felt part of this country. In the days of terrorism we would day that Inca Kola was the flavor that united us, it gave us strength, when the times of pain passed, it became the flavor of joy, the flavor of the party. When confronted with copies [Isaac Kola] we said that Inca Kola was the national flavor. We always made that distinction, we have always felt proud of Peru”.

–Johnny Lindley

Continue reading →